What can be patented is a question that inventors often ask. It is always better to have a heads-up on what can be patented to determine the patentability of an invention before filing for a patent. Our previous blog post on what can be patented has comprehensively explained the patentability requirements. The patentability requirements may be summarized below:

1. Novelty

2. Non obviousness

3. Capable of Industrial Application

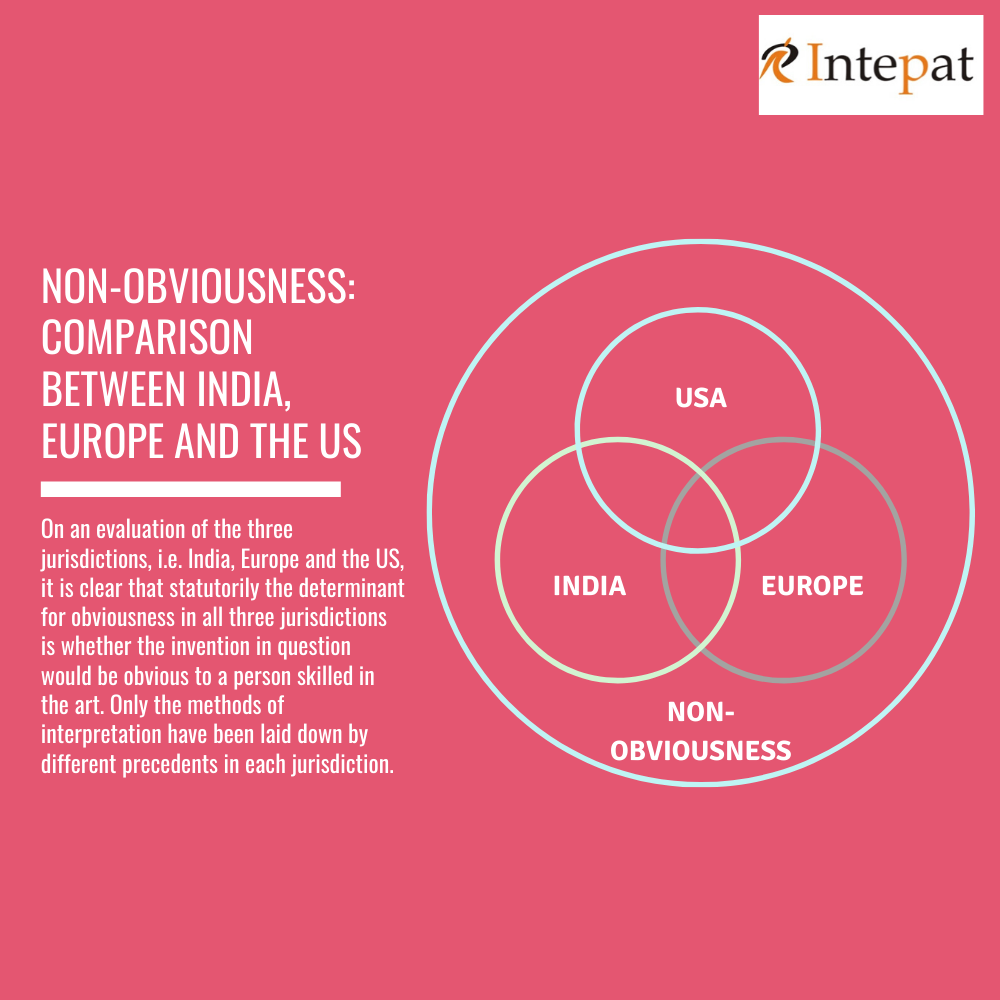

Of the requirements mentioned above, the provision of “non obviousness” is relatively controversial, given that there is no standard for determining whether an invention is obvious or not. Non obviousness in a patent means the invention must not be obvious to a person skilled in the same field as the invention relates to. This is, therefore, a subjective requirement that varies from one invention to another. To circumvent this subjectivity, different jurisdictions have adopted other criteria for determining whether an invention was obvious or not.

India:

The nonobviousness/ inventive step criteria are defined under Section 2(ja) of the Patents Act, 1970, as “a feature of an invention that involves technical advance as compared to the existing knowledge or having economic significance or both and that makes the invention not obvious to a person skilled in the art.”

The statutory definition only goes as far as stating that to be patentable; one requirement is that the invention must have a ‘technical advance’ or ‘economic significance’ in comparison with the prior arts, thus making the invention nonobvious to a person skilled in the same field as the technology relates to. The definition gives scope for subjectivity in terms of interpretation.

The Supreme Court, in the case of Bishwanath Prasad Radhey Shyam v. Hindustan Metal Industries (13.12.1978), interpreted the term inventive step. In this case, the court opined that ‘obviousness’ has to be strictly and objectively judged. The test laid down by the court to determine obviousness was:

‘Had the document been placed in the hands of a competent craftsman (or engineer as distinguished from a mere artisan), endowed with the common general knowledge at the ‘priority date,’ who was faced with the problem solved by the patentee but without knowledge of the patented invention, would he have come up with the invention in question

According to the test, what has to be determined is whether, at the time the invention was made, any other person skilled in the same field as the invention could have come up with the same invention if faced with the same problem.

Even though the case was decided in 1978, its relevance of the case has not diminished with time. Therefore, in India, the statute defines inventive steps, and the judicial precedent provides an objective interpretation of the requirements for determining the obviousness of an invention.

Europe:

The European Patent Convention states that for an invention to be patentable, it must be new and involve an inventive step.

Article 56 of the European Patent Convention envisages the meaning of ‘inventive step.’ The Article reads: “An invention shall be considered as involving an inventive step if, having regard to state of the art, it is not obvious to a person skilled in the art.”

As seen above, the EPC does not elaborate on the criteria for determining whether an invention is obvious. The Boards of Appeal of the European Patent Office solved this dilemma by evolving a problem-solution approach for assessing the obviousness of an invention.

The problem-solution approach is employed in three stages:

1. Choose the closest prior art- the closest prior art in this context refers to prior art that belongs to the same technical field as the invention in question, and it must be the most similar prior art available.

2. Determine the technical problem- in this stage, the technical problem that the invention addresses and solves must be determined. This stage also involves determining the technical differences between the invention and the closest prior art.

3. Examine the solution- the solution to the persistent technical problem must be assessed for obviousness. In other words, what must be evaluated is whether the solution proposed by the invention is obvious to a person skilled in the same field as the invention. In this stage, it must be assessed whether anything in the prior art could or would prompt a person skilled in the art to find a solution to the technical problem, thus coming up with something identical or similar to the invention in question.

Thus, in Europe, the problem-solution approach is used to determine the obviousness of an invention.

USPTO:

35 U.S. Code § 103 lays down the conditions for patentability concerning nonobvious patents. It reads as follows: “A patent for a claimed invention may not be obtained, notwithstanding that the claimed invention is not identically disclosed if the differences between the claimed invention and the prior art are such that the claimed invention as a whole would have been obvious before the effective filing date of the claimed invention to a person having ordinary skill in the art to which the claimed invention pertains.”

The United States Supreme Court interpreted and explained this provision in the precedent Graham vs. John Deree. The Supreme Court formulated the following guidelines to determine the obviousness of an invention:

1. Determine the scope and content of prior art

2. Analyze the differences between the prior art and the invention in question

3. Determine the level of ordinary skill in the pertinent art

4. Ascertain the secondary considerations of non-obviousness. Secondary considerations like a long-felt but unmet need for a device or the failure of others to solve the problem addressed by the invention in question suggest that a patent must be issued, even if the invention in question seems obvious.

The U.S. Courts have envisaged multiple ways of determining the obviousness of an invention. The above-stated precedent can still be used to determine obviousness.

On an evaluation of the three jurisdictions, i.e., India, Europe, and the U.S., it is clear that statutorily the determinant for obviousness in all three jurisdictions is whether the invention in question would be obvious to a person skilled in the art. Different precedents have laid down only the methods of interpretation in each jurisdiction.

[cherry_button text=”Need help? Connect with experts” url=”https://www.intepat.com/contact-us/” style=”link” size=”large” centered=”yes” fluid_position=”right” icon_position=”top” bg_color=”#f79351″ min_width=”33″ target=”_blank”]